The Cross And Christianity

Symbols, History, and How the Church Got Here

It was probably about a year ago when I was having lunch with a close friend of mine who happens to be a Christian pastor. I was wearing a black hoodie with the Star of David on the front, and inside the star were the words of the Shema — one of the most sacred declarations from the Tanakh:

“Hear, O Israel: Yehovah our God, Yehovah is one.”

As we talked, he asked if I was aware that the Star of David had pagan connections before it became associated with Judaism. He wasn’t wrong. The symbol does predate Judaism, though it was never tied to any single pagan deity. Still, his question stuck with me.

I explained that while the Star of David is commonly used today to represent Judaism, it was never regarded in the same way the cross is regarded within Christianity. That conversation sent me down a much deeper path of research into religious symbols, their origins, and how they came to represent entire faith systems.

Asking the harder question

As someone who has become Torah-observant, I’ve learned that asking deeper historical questions is unavoidable. One of the first questions that hit me was this:

When did the cross actually become the symbol of Christianity?

And even more importantly:

Would Jewish followers of Yeshua really have embraced a symbol tied to Roman execution and public humiliation?

After all, crucifixion was one of the most brutal punishments Rome used — often carried out publicly against Jews. That reality alone should make us pause.

The earliest believers and their symbols (30–70 CE)

In the earliest period following Yeshua’s resurrection, the movement that followed Him was still thoroughly Jewish. It functioned within Jewish life and thought, and it existed under constant pressure and persecution.

Because of this, symbols had to be subtle and discreet.

The earliest imagery associated with believers during this period includes:

- The fish (Ichthys)

- The shepherd or lamb

- The anchor

- The menorah, especially among Jewish believers

These images communicated meaning to those “in the know” but appeared ordinary to outsiders. Notably, there is no evidence of crosses being used during this period.

The absence matters.

After 70 CE: identity under pressure (70–200 CE)

Following the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE, both Judaism and the Yeshua-following movement were forced to adapt. Believers were still persecuted, still marginalized, and still cautious.

During this period, we continue to see:

- Fish imagery

- Anchors

- Shepherd symbolism

- Lamb imagery

Interestingly, the shepherd motif gradually fades, sometimes replaced by the lamb alone.

Still, no crosses appear.

This tells us something important:

the early believers understood the message of Yeshua without needing a symbol of execution to represent it.

The third century: a transitional period (200–300 CE)

By the third century, the movement had grown significantly and had become increasingly Gentile in makeup. It was still illegal, but its identity was beginning to shift.

During this period we begin to see new symbolic forms:

- The Tau (Τ)

- The staurogram (a ligature of Greek letters used in manuscripts)

- Anchor-like forms that subtly resemble a cross

These are not public devotional symbols. They appear mainly in manuscripts or indirect forms.

Importantly, the traditional lower-case “t” image, commonly known as the Latin Cross still does not appear as a dominant or devotional image.

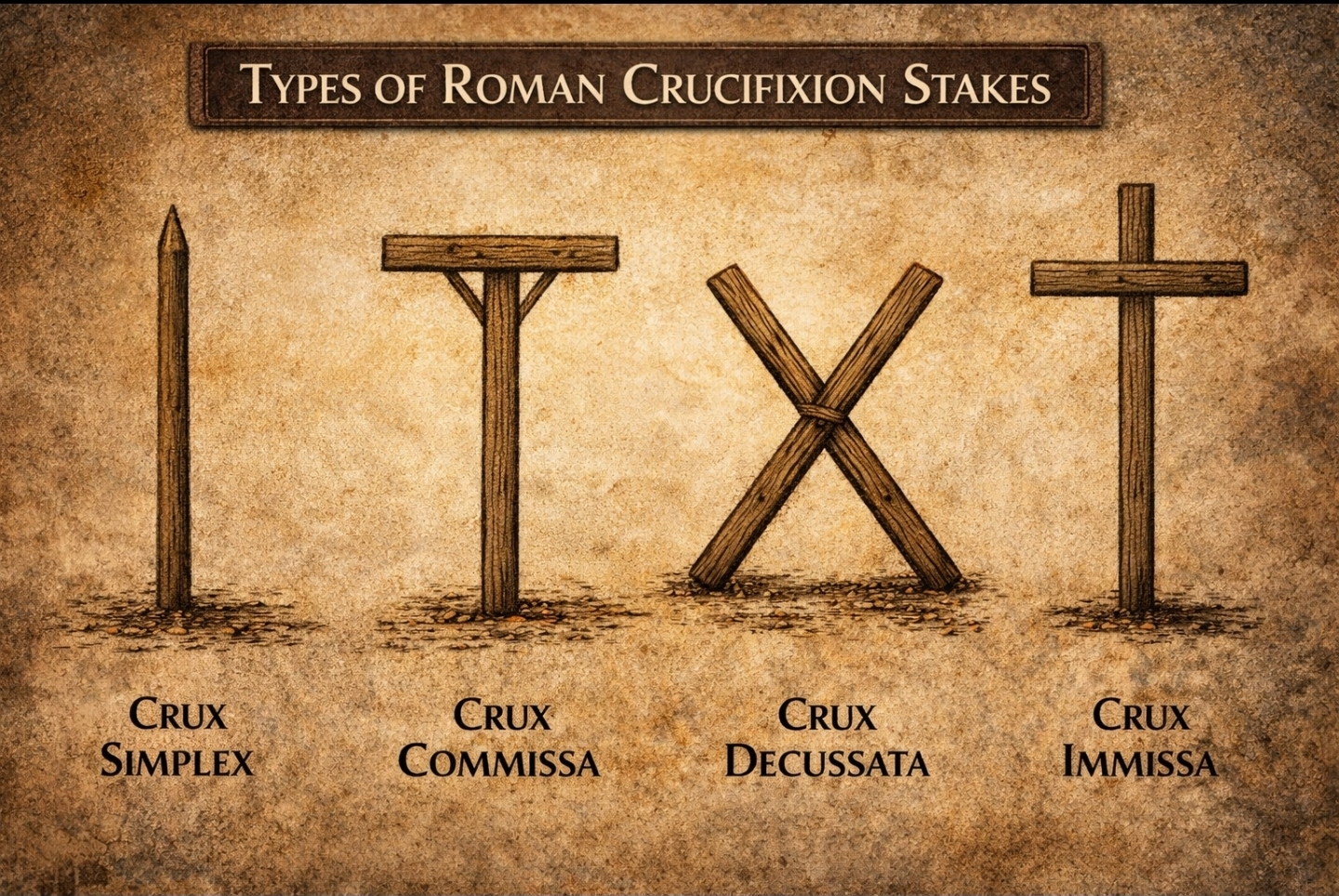

It’s also worth noting that Scripture never specifies the exact shape of the execution stake used for Yeshua. Historically, Rome used several forms of crucifixion. The idea that it must have been the later Latin-style cross is an assumption that developed much later.

Constantine and the turning point (312 CE)

Everything changes in the early 4th century.

In 312 CE, just before the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, Emperor Constantine reportedly experienced a vision. According to the earliest sources, he was instructed to use a symbol associated with Christ.

Again, that symbol was not a cross.

It was the Chi-Rho (☧) — formed from the first two Greek letters of Christos.

Constantine ordered this symbol to be placed on military standards and shields. This marked the first time a Christian-associated symbol was used publicly and imperially.

In 313 CE, Constantine legalized Christianity through the Edict of Milan. Later emperors would go even further, eventually making Christianity the official religion of the empire.

A major shift in direction

By the 4th century, the church had become overwhelmingly Gentile. Jewish believers were now a minority, and Jewish perspectives were increasingly pushed aside.

In 325 CE, the Council of Nicaea met to address theological disputes. While this council did not invent the cross, it represents a turning point where church identity became centralized, imperial, and increasingly separated from its Jewish roots.

Over the remainder of the 4th century, something significant happens:

The cross begins to appear openly and publicly.

By this time:

- Crucifixion had been abolished

- The shame associated with the cross faded

- Christianity had political power

- Symbols became tools of unity and authority

Eventually, the cross became the defining emblem of Christianity.

A late development — NOT an apostolic one

By the late 4th and 5th centuries, the cross had become widespread. Later still, the crucifix (a cross with a body) emerged in Christian art.

What’s important to understand is this:

The cross was not a symbol handed down by the apostles. It developed centuries later as Christianity became institutionalized. This doesn’t mean people who revere the cross are acting in bad faith. But it does mean the symbol itself is a historical development, not a biblical command.

A personal reflection

Learning this history changed how I see things. When I compare the cross and the Star of David, I now see both as symbols shaped by history rather than divine mandate. Still, knowing that the cross emerged during a time when Gentile leadership had fully overtaken the movement — and when Jewish voices were largely absent — makes me pause.

For me personally, it explains why the cross no longer carries the same weight it once did. I don’t see symbols as possessing inherent authority. What matters is obedience, faithfulness, and walking out the way of God as revealed in Scripture.

That’s why I find myself more comfortable wearing the Star of David than the cross — not because it is commanded, but because it better reflects where my convictions now rest.

I share this not to persuade, but to explain the journey.